Iliotibial Band Syndrome

A Common Cause of Knee Pain in Runners & Multi-Sport Athletes

What is Iliotibial Band Syndrome?

Iliotibial Band (IT Band) Syndrome (ITBS) is the most common cause of knee pain in runners, by some estimates accounting for 12% of all running-related injuries. While ITBS is not quite as common in bicyclists, it does occur, and at the very least the multi-sport athlete who develops it with running may continue to aggravate it on the bike. ITBS is commonly labeled as an "overuse" injury. However this is really a misnomer, as it is generally not the fact that the knee is being used too much but rather that there are predisposing biomechanical factors causing injury with even appropriate levels of training.

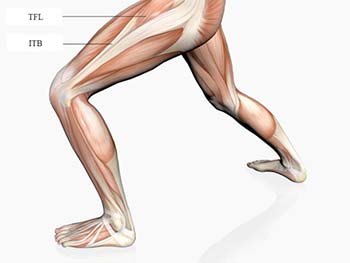

ITBS occurs when the IT Band, basically a long tendon arising from the tensor fasciae latae (TFL) and gluteal muscles and running to the outer part of the knee, frictions against the outside edge of the knee joint (lateral tibial or femoral condyle.) With time and continued use, the portion of the IT Band that frictions become inflamed and painful. The pain is typically most pronounced when running, especially when going downhill. During a run the pain is classically felt on the outside of the knee about one inch above the crease. However, pain can be felt anywhere on the outside of the hip down to the knee and still technically be called ITBS. ITBS usually responds well to appropriate conservative (non-surgical) treatment. However if the condition is not treated and the athlete continues to aggravate it, ITBS can become more disabling with time and require further intervention such as cortisone injections or in extreme cases even surgery.

ITBS occurs when the IT Band, basically a long tendon arising from the tensor fasciae latae (TFL) and gluteal muscles and running to the outer part of the knee, frictions against the outside edge of the knee joint (lateral tibial or femoral condyle.) With time and continued use, the portion of the IT Band that frictions become inflamed and painful. The pain is typically most pronounced when running, especially when going downhill. During a run the pain is classically felt on the outside of the knee about one inch above the crease. However, pain can be felt anywhere on the outside of the hip down to the knee and still technically be called ITBS. ITBS usually responds well to appropriate conservative (non-surgical) treatment. However if the condition is not treated and the athlete continues to aggravate it, ITBS can become more disabling with time and require further intervention such as cortisone injections or in extreme cases even surgery.

What Causes ITBS?

One potential cause of ITBS relates to ergonomic issues in running and biking. This can include, for example, prolonged running on cantered surfaces such as the side of the road (the left leg is usually affected when running against traffic.) Excessive running on a track can create asymmetrical forces in the lower extremities, because you are always running (and slightly leaning) in the same counter-clockwise direction around the curves. On the bike, two common issues are riding in clipless pedals that force the foot to toe-in (more of a problem with older-style pedals that don't float) and/or an improper seat height.

In the absence of (or in addition to) ergonomics ITBS most often results from some combination of two biomechanical factors: tight hip abductors (especially the TFL) and excessive internal rotation of the tibia. Tightness of the TFL leads to tractioning and tautness of the IT Band. Internal tibial rotation pulls the lateral condyle into position to friction the taut band. The net effect is that the lateral condyle "snags" the IT Band as it passes by with each step or pedal stroke, usually at around 30* flexion of the knee.

The underlying cause for both tight hip abductors and excess tibial rotation almost always relates to biomechanical faults of the lower extremity that becomes a factor during the gait cycle. In fact, it is rare to find hip abductors tight enough to cause ITBS without having some type of mechanical fault on the affected side. (This explains why stretching alone is rarely enough to get rid of an established case of ITBS). The two most common mechanical faults are hip joint restriction and foot dysfunction.

The hip joint (the actual ball and socket, or femoral-acetabular joint) is a common area of tightness and restriction. Many endurance athletes have tight hip flexors and adductors, which tend to hang up the range of motion of the hip. If the hip joint is overly restricted it can actually inhibit, or turn off, certain muscles, especially the gluteal medius and hip flexor. The gluteus medius serves to stabilize the hip during the stance phase of gait, preventing the leg from collapsing inwards towards the opposite leg. The hip flexor helps to lift the leg during the recovery phase of gait. The TFL to some degree actually assists both the hip flexor in flexion and the gluteus medius in abduction. Of the several different scenarios in which the hip complex factors into ITBS, one of the most common is a weak/inhibited gluteus medius and/or hip flexor and strong but over-compensating TFL. With time the over-worked TFL becomes tight which then translates into the IT Band. There have been studies demonstrating a correlation between ITBS and weak hip abductors on the affected side.

Foot dysfunction is the other primary underlying factor in the development of ITBS. By dysfunction I mean any mechanical abnormalities within the foot and ankle that prevent them from doing their job. Quite often there will be muscle imbalance between the peroneals and deep foot/toe flexors within the lower leg. These muscles form a "stirrup" around the foot and support it as it comes into contact with the ground. Anything that prevents these muscles from firing not only strongly but also in the proper sequence (proprioception) will have a negative impact on the foot mechanics during running. The most common scenario I see relating to ITBS is weakness and/or proprioceptive deficit (i.e. residual from an old ankle sprain) of the peroneals, coupled with tightness of the deep flexors, leading to a compromise of intrinsic arch support and consequent over-pronation during gait. Over-pronation can be the result of other factors, but whatever the source, it will lead to increased internal rotation of the tibia at foot-strike, which then stresses the IT Band attachment.

While hip and foot dysfunction are the most common contributing factors of ITBS (as well as other sports injuries), they are often not adequately addressed. This is unfortunate because they can be directly linked to the two causative factors in ITBS.

So in summary, a common scenario in the development of ITBS includes: Mechanical fault(s) in the hip and foot, inhibited/weak peroneals and hip abductors, over-pronation and tightening of hip abductors, excessive tibial internal rotation, friction between lateral condyle and tight IT Band during knee flexion, inflammation and pain.

Treatment

In the treatment of ITBS it is important to obtain an understanding of the entire biomechanical picture, and not just direct treatment to where it hurts. Gait analysis and manual muscle screening help to reveal what's weak and what's tight. Evaluation of the relevant joints helps to uncover joint dysfunction along the kinetic chain and helps to differentiate between muscle weakness and inhibition. Employing Active Release Technique as not just a treatment tool but as a diagnostic aid helps to isolate exactly what portion of the IT Band is involved, and whether the surrounding muscles such as the outside quads or hamstrings are involved. The earlier in the treatment process we can identify all of these relevant potential complicating factors the better our results will be.

Once we have an idea of the overall picture, treating ITBS involves a three-part strategy not unlike treating many other soft-tissue disorders:

- Acute care measures to reduce inflammation. This typically involves icing the knee after runs, possibly NSAIDs, and some degree of modification of training, depending on the severity of the condition. The biggest effect obviously will be on running, and can range from a slight decrease in miles and intensity to totally taking off days or even weeks. With biking there are more available modifications to possibly allow for unaltered training. For example, spacers can be inserted between the pedal and the crank, which effectively puts the tibia in external rotation. Fortunately swimming will generally not aggravate ITBS, so it could be a good time to increase training in the pool. Overall the earlier in the process treatment is sought, the less training will be affected.

Unfortunately many athletes with ITBS (and other sports injuries) are just told to stop training and rest. In all but severe cases I believe that this is counter-productive. Virtually any "over-use" injury will respond to rest. However until the source of the problem is identified and addressed, it quite likely to return with resumption of activity. Quite often I will recommend some reduction in training, or at least substitute in some cross training (i.e. cycling in place of running two days a week.) However if possible I find it better to continue some semblance of training so that the athlete maintains conditioning and so that we know that any results obtained are due to the treatment and not just rest.

- Increasing flexibility of the tight tissue. Any number of soft-tissue release techniques can work. I will often utilize a combination of techniques, such as trigger point therapy, Active Release Technique(R) (A.R.T.), cross-friction massage, and post-isometric relaxation stretching to both the hip abductors and the ITB itself. A.R.T. in particular is very effective at breaking up adhesions within the ITB and between it and the outside quad. Home stretching exercises will also typically be given (see 'prevention'). In addition, the same factors that cause ITBS will also frequently cause other issues, particularly tight hip flexors and sacro-iliac joint dysfunction. These will need to be addressed as well.

- Identifying and correcting the reason the structures are tight and/ or weak in the first place. This would include addressing any of the previously mentioned ergonomic issues. Beyond that the cause will usually relate to faulty hip and/or foot mechanics. For both I will typically work on both the joint and muscle aspects of the problem with manipulation and any of the various soft-tissue techniques listed above.

Prevention of ITBS

Of course prevention is always the best medicine. For the most part this consists of common sense running ergonomic issues. Avoid large jumps or sudden increases in training. Try to minimize running on cantered surfaces, and try not to always run on asphalt. If you do a lot of track work-outs try alternating the direction you run every so often.

Running shoes are critical: ensure that yours are appropriate for your running style (over-pronation being by far the most common issue), supportive enough, and not too worn down. A generally accepted number for the life span of a running shoe is 500 miles. If you put in a lot of miles running, alternating between two pairs of shoes will increase the life span of both during a season. If you are unsure if your shoes are right for you, try a technical running store, where they are more knowledgeable about matching up your particular gait mechanics with the right shoe.

It is worth looking into your running form, especially if you have never paid much attention to it. The most common form flaw is heel-striking, which accentuates pronation and allows more jarring force to translate up into the knee. Heel-striking is usually the result of over-striding and/or a lack of engagement of the core during running. "Chi Running," a book on running form, can is an accessible way of learning the principles of good running form. (Note: Transitioning away from heel striking takes time and practice. If you already have IT Band issues changing your running technique mid-season might be too much for the body to handle. You may need to wait until the condition is less acute.)

One of the studies showing a link between weak hip abductors and ITBS also seems to show that regaining abductor strength helps to prevent the return of the condition. In my experience this is true; a weak gluteus medius in particular is a factor with many hip and knee issues in general. In fact I would say that weak/ inhibited gluteals are one of the most common biomechanical factors I see with almost any type of running injury, even with some foot issues. As mentioned previously weak hip abductors lead to them becoming tight due to over-compensation. The key to maintaining flexible hip abductors, and therefore helping to prevent ITBS, is to keep them strong.

I have included a handout of some of my favorite hip exercises including several that utilize resistance bands. These are an inexpensive yet effective training tool that allows you to work the hip muscles in a standing position. These so-called "closed-chain" exercises (foot in contact with the ground) are the most effective way of building sport-specific strength that translates into injury-prevention and performance. I would suggest doing the strengthening portion of this routine 2-4 times a week; a good goal is to build up strength in the off-season and then maintain it during the running season by doing them 1-2 times a week. The squats shown can probably be skipped if you do a lot of biking.

For those who have tight hip abductors stretching them is obviously helpful. To the left is a stretch you can use to screen for tightness of this muscle group. In this case, the right TFL and IT Band are being stretched by using the left foot to push the knee down. This stretch requires a fair amount of tightness to be felt; as a rule of thumb, if you do feel the stretch with this exercise then you are too tight. Add this to your regimen until you get to the point where you don't feel much happening, and then progress to a harder stretch. If you can't get your knee to the ground with this stretch then you are definitely too tight.

For those who have tight hip abductors stretching them is obviously helpful. To the left is a stretch you can use to screen for tightness of this muscle group. In this case, the right TFL and IT Band are being stretched by using the left foot to push the knee down. This stretch requires a fair amount of tightness to be felt; as a rule of thumb, if you do feel the stretch with this exercise then you are too tight. Add this to your regimen until you get to the point where you don't feel much happening, and then progress to a harder stretch. If you can't get your knee to the ground with this stretch then you are definitely too tight.

The next progression for IT Band stretching is shown on the hip handout (the one lying on your back and using a belt to pull the leg across.) If you can do this and bring your leg all the way to the floor without much of a stretch then you probably don't need to worry about stretching your IT Band. Another stretch on the handout (gluts: supine) isolates more the gluteals including the gluteus medius. Since tightness of these muscles is usually the source of the IT Band itself being tight, they should be stretched also.

On the bike, fit is everything. In particular make sure that the pedal and shoe cleats are properly aligned and that the seat height and fore/aft positioning are correct. A bike shop can help you make sure you're set up is correct.

ITBS is largely preventable. When it does occur, it generally responds well to treatment. If you do start to develop pain on the outside of the knee or hip, don't wait too long before having it looked at. The earlier it is treated the quicker it will respond, and the less training time you will lose. Good luck and happy, healthy training.

Jamie T. Raymond, D.C. is a Certified Chiropractic Sports Physician and Active Release Technique provider in Portland, ME. For more information on A.R.T. visit: www.activerelease.com. Or feel free to talk to him at the up-coming Bath, Poland, and Freeport triathlons, where he is scheduled to provide A.R.T. treatments.